September Musings

Yuma friends,

Thank you for being here. This is a place where I will share my current practice, as well as work by others that is lighting me up. It is the main place where I will be sharing my work for a while: as I recalibrate and reimagine a practice that is sustainable and joyful.

The title, “the Crepuscular Hour” comes from a twice-daily phenomenon: the light just before sunset and just after sunrise.

You can listen to the audio version of this newsletter here:

Where you can catch me and my work

Loom Literary Journal

Artist Sammy Hawker and I recently had a piece published in Loom Literary Journal. I'm very proud of it. It's a lovely little piece, with beautiful photographs from Sammy. The online piece will be published shortly. In the meantime, you can order a hardcopy online at the Loom Store. You can also pick them up from Book Cow in Canberra, or Brunswick Bound and/or the Paperback Bookshop in Naarm/Melbourne.

A prescription for petrichor, the smell of rain

- In a dry time, wait for rain.

- When you know rain is coming, sit outside as the weather changes.

- Smell.

- Notice the smell in your whole body. The front and back of your head. Your spinal column, your soft belly, your toes, your fingers.

- Breathe the smell in and out until you mingle entirely with it.

Variation:

- Find a rock.

- Place it somewhere where it will naturally become dry. Perhaps on a verandah.

- When it is very dry, water it with a watering can.

- Repeat steps 3-5 above.

I remain sick. The body breaks. Two months into illness, my life has become a sabbath, a pause. An emptiness into which sacredness might flow. I cajole my partner into a walk on Country, but two hundred metres from the house, find myself unable to walk. The body breaks. We lie on our backs, looking at the sky, which bruises. The air curates the scents and sounds around us: sweet caramel early wattle, wamburang (black cockatoos), and the scent of wet. I love these damp moments when the sky and earth seem to cleave each other. This wildness, the greatest comfort to me, lulls my sick body towards sleep. I breathe deeply. Ah, I think, petrichor.

Breath is a good language for soil–human communication, because the primary language of soils is chemical. In soil’s own world, chemicals are queen. If we imagine seeing the world as a soil critter, we find a world of near-total darkness. A world in which air can have nearly 100% humidity. Chemical sensing—chemosensation—separates prey from predator.

The term petrichor was originally conceived quite close to where you and I are slowly falling asleep on the ground. In 1964, CSIRO scientists Isabel “Joy” Bear, and her senior colleague, Dick Thomas, published a Nature paper that coined the term. Petra for rock, and ichor, variously translated as “tenuous essence”, and “ethereal fluid.” It was Bear and Thomas who first discovered that this petrichor smell would emanate from “the vast majority of dried silicate minerals and rocks.” Only a year later in 1965, over at Rutgers in the USA, scientists Nancy N. Gerber and Hubert A. Lechevalier would describe an almost synonymous name, for an almost synonymous smell. Geosmin, from the Greek ge, or earth, and osme, or smell. The term describes the “typical odour…of freshly plowed soil”. A particular chemical compound derived from bacteria, geosmin is the “earthy” smell in food, particularly beetroots. Geosmin is also one of the core smells of petrichor.

Scientists believe that petrichor may be spread by gusts of wind. A team at MIT filmed hundreds of drops of water hitting the earth, and analysed them in slow motion. What they found was a “frenzy” of tiny aerosols, dispersing upon impact. These projected tiny volatiles into the air: spores, bacteria, geosmin, the parcel of smells behind petrichor. I may not be smelling the soil I am lying on, but rather, the soil nearby.

There was a time when early chemists thought we might come to know soils not by their sight or texture, but by their scent. In the late 1800s, Parisian Chemist Michel-Eugène Chevreul studied the formation of his local soils by smelling macerated mud samples.

To me, the world in rain smells fresh, and slightly green. Grassy. The thick scents of pollen that have marked recent days are temporarily transmuted into the smell of wet soil. I am lying on the grass outside my house in the drizzle. My body is perforated with heaviness. Illness. Grief. Anxiety. The small clod of earth between my fingers is almost sweet when I pull it up. I welcome the raging storm as a changing of the guard.

You can read about more of my art inspired by petrichor here on my instagram.

Here is a lovely Conversation article on Geosmin.

What Country is doing now

It is my favourite time of year: the simultaneous joyful flowering of so many pea plants. The wattles are effervescent with life, everywhere I look is enthusiastic yellow. Beneath my feet is the subtle violet of twining glycine, the royal purple of hardenbergia, and the sweet little red and yellow egg-and-bacon flower. Abundant rains have overflowed the dam, and nearly submerged the jetty. A tiny waterfall flows into our sedges.

What I’m wild harvesting now

Inspired by this journal article, I have started brewing up a little silver wattle tea, from the plant’s early buds. I use a ratio of about 10% buds, to 90% room temperature water. If left for around twenty-four hours, the brew is subtle, sweet, and apparently chock-full of antioxidants. I made a little video about the experience.

I’m sure I was unconsciously inspired to make this brew by my landmate, activist cook, Sam Hawker’s (no relation to artist Sammy Hawker!) lovely wattle cordial, you can find her work here.

If you're interested in other uses for wattle, the book Ngunnawal Plant Use is a great starting point.

Always Was, Always Will Be

Speaking of beautiful Ngunnawal Country, my partner Kass, our landmate Sam, and I recently had the pleasure of going to the Watermarks Community Event at Sullivan’s Creek in central Canberra, to celebrate the installation and revitalisation projects that the Ngunnawal community have been leading along the dry creek-bed. It was a beautiful night, and my highlight was walking along the creek, and seeing the art installation that the community had made along the enclosed creek's concrete side. The installation is accompanied with a song penned by the talented Ngunnawal Composer Alinta Barlow. If you are in the Canberra area, you can check out the installation yourself, it starts near the Quaker Meeting House in Turner. You can read more about the project here.

In addition to our annual cultural burn, I had the pleasure this past week of attending two more cultural burns guided by the excellent team at Waluwin Ngurambang. It was a delight to see the kookaburras and maggies gathering around to catch all the little insects that scurried away from the flames, to smell the scent of fire on Country, to meet all the lizards coming out of their brumation. We have been working with the Waluwin Ngurambang team since 2022, and I cannot recommend them enough for all your caring-for-Country needs. They are a lovely Wiradjuri-owned family business, and each of them has more knowledge about Country in their little finger than I gained in an entire PhD in soil studies.

Your Christmas Book List

Don’t know what to get for your single lesbian aunt? Your autistic, socialist, office BFF? Your cousin who can identify all the plants? I got you.

I am a recovering insomniac and Weird Kid: I read an unusual amount. I am constantly reading absolutely brilliant books that are far less famous than they should be. I’m here to rectify that. You’re welcome.

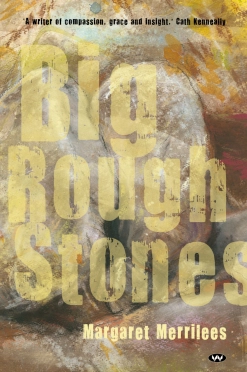

September’s feature is: Big, Rough Stones, by Margaret Merrilees

Buy for: your girlfriend, your cousin who just came out, your lesbian aunt.

Pairs well with: Stone Butch Blues, Rubyfruit Jungle, lesbian love triangles, fighting with your housemates about smoking indoors.

If anything is proof that the literary world is not a meritocracy, it is the absolute crime that this book isn’t famous yet. Big Rough Stones follows Ro, our deeply human, and somewhat unreliable narrator through her early years in Adelaide’s 1970’s lesbian scene, to her eventual diagnosis of terminal illness in the 2010s. This is a book about the beautiful experiment of living a life through counterculture. Through Ro’s often stubborn and didactic eyes, we see a life that is genuinely built around the messiness of community, and the desire to experiment another way of living. We watch as Ro’s, and her community’s, values change as they live their lives. How Ro discovers very quickly that the grubby, dangerous realities of the lesbian back-to-the-land movement don’t match her romantic ideals. How Ro doesn’t believe in heteronormative, monogamous ownership of another, yet also finds herself shaken by jealousy. How Ro’s initial cynicism of performing the masculine gives way to admiration as her best friend establishes herself as a drag king.

Big Rough Stones shows the chosen family of older lesbians in all its complexity. The decades-long disagreements. The decades-long longings. Eventually, as Ro moves into palliative care, her paramours and metamours become the people who feed her, walk her, bitch about her, love her. We see the overwhelm Ro’s friends feel at caring for her. It’s an unflinching description of alternative models of care.

Part of why I love this book is that it shows us so much about where we come from, and the gains that were made by second-wave feminists. I’m reminded of how far we've come when our central clique has to hide from a potentially violent group of drunk men in 1970s Victoria. I’m reminded again, when one character tries to undergo a gender transition synchronous with menopause and can’t find a doctor to help.

I am also a total sucker for any book about activist history. I find it so joyful (and a little stressful) to see how the same problems with non-hierarchical organising that we deal with today have dogged us since the 1970s. I also loved the retelling of some of the more famous queer, environmental, and anti-empire protests, particularly the famous Pine Gap protest of 1983, where 111 women gave the name "Karen Silkwood" when arrested, honouring the American Union activist who died under suspicious circumstances in 1974.

My one sadness about this book is the lack of trans women. I suspect that the queer feminist world of Margaret Merrilees simply had no trans women in it, and I believe it would be overstating the inclusivity of the movement to pretend otherwise. Merrilees has done a good job in walking a fine line between acknowledging the importance of trans* experience in the movement without pretending that second-wave lesbianism was particularly inclusive. I admire the honesty, but the reality still leaves me sad.

That said, this book helps us to understand our present through exposition of our past, it is a gift to the younger generations of queers. It is a peek into the complex, flawed, beautiful, problematic, utopic, generous elders and movements that made our world possible. Also, it will probably make you cry. This book should be on the bookshelves of every queer and ally in Australia. Buy this book.

Other Good Things

My brilliant friend, Izzy Roberts-Orr just had a lovely poem, the museum of wronged women, published in the literary journal Meanjin. Like Izzy, I have been waiting for fifteen years until I have something good enough to submit to Meanjin, Like Izzy, I am devastated by Melbourne University Press's decision to close the 85-year-old Magazine. You can follow the campaign to save Meanjin here.

And sometimes we do save things! After a three-month exhausting fight, the Australian National University's Environment Studio has been saved, along with the tenure of the brilliant Amanda Stuart. This is one of the only courses offered at ANU that teaches proper way fieldwork, centring Aboriginal leadership. You can check out the program's archive here. After my own small contributions to the fight to save the Environment Studio, I am taking a long, grateful exhale.

My best friend, Tamuz Ellazam, is the incoming manager for Readings Kids in Carlton, Naarm/Melbourne. Tamuz's Master's thesis focused on representation of underserved populations in children's books. I cannot imagine a better person for the job. Go buy books from her for your little monsters!

Mutual Aid

Kass and I are big fans of the Climate Justice Union, who do powerful advocacy work for underserved populations affected by climate change. They do not receive as many donations as they should because they do not have charity status. You can donate directly, and you can also become a member.

If you have a mutual aid request that you would like me to post in the October Newsletter, please get in touch.

Thank you,

If you feel moved by anything in this newsletter, and want to forward it to a friend, that would genuinely help my practice grow.

Love and solidarity,

Flo Sophia Dacy-Cole