November Musings

Yuma friends, thank you for meeting me here. This is the place where I share my current practice, as well as the work of others that are lighting me up. The title, the Crepuscular Hour comes from a twice-daily phenomenon: the light just before sunset and just after sunrise.

For those of you who prefer the listening experience to the looking experience, you can listen to the audio version of the newsletter on Soundcloud.

A prescription for the insatiable thirst of pregnancy

First, you begin to feel queasy.

Then you begin to feel exhausted.

Then you begin to feel desiccated. Pruned, even.

Your body is creating fifty percent more blood. You become a husk. You develop dandruff in your eyebrows.

You dream of becoming a salamander. A seasponge. Of water flowing through you.

Then you begin to drive, compulsively, to the Mongarlowe.

Every spare day, every spare afternoon. Over the great dividing range, through Braidwood, past Plumwood’s beloved mountain, to the Monga National Park.

The park feels rough, harsh. You wander through it, hearing Bird Rose’s words over and over again in your head “wounded places, wounded places.”

You think there are some parts of Country that are so longing to be held, so longing for care that it’s palpable. There’s a spookiness to the longing, a wariness in the soil. In Monga, all the old walks among the plumwoods are covered with the dense scrub of post-fire rainforest regrowth. In Monga, the silence is too deep.

Yet every single part of Monga feels sacred. From the wildflowers that exploded all spring, while you stumbled full of nausea along its paths, to the swallows that teased you, divebombing your head as you waded thigh-deep through the river.

The Mongarlowe! The call that brought you back, and back, and back. The entirely clear water. The freeze of it: a rare antidote to queasiness.

Here is what you need to do if you are beset by the insatiable thirst of pregnancy:

- Drive to the Mongarlowe, or another rainforest river.

- Walk inside the river until you find the perfect spot.

- This is the perfect spot: a spot between the ferns along the bank. Lie down, leave your feet in the water.

- Slowly, swap the atoms of your body with the atoms of the wet soil underneath you.

If you haven’t yet mastered the art of atom transfer, here’s an alternative:

- Drive to the Mongarlowe, or another rainforest river.

- Collect a billy can of water from the river. Boil it. Wait a little for it to cool.

- Walk inside the river until you find the perfect spot.

- This is the perfect spot: a spot between the ferns along the bank. Sit down, leave your feet in the river.

- Feel how the river moves your legs, your toes.

- Put all of your awareness into your legs, your feet, your toes.

- Drink all the water in the billy can.

- Repeat

What Country is doing now

The last of the egg and bacon flowers are blooming. Egg and bacon flowers are a generic term that describe many different types of native pea plant. They are incredibly diverse, but all characterised by a host of tiny yellow or orange flowers with a red heart. They are delicate, exuberant, cheery. Being pea plants, they are soil rescuers, and close to my own heart. Every year, I spend all spring falling madly in love with them.

What I’m wild harvesting now

There is so much to harvest in this liminal spring/summer season, but I am, once again, stuck on cassinias. Native to Australia and New Zealand, cassinia is a species of approximately 52 flowering shrubs and small trees in the asteraceae, or daisy, family. We have at least three types on the property: the much maligned cassinia sifton, or sifton bush; cassinia quinquefaria, also known as dogbush; and cassinia longifolia, or cauliflower bush. The latter two are sometimes called “native rosemary”, although they are from a different plant family. I suspect this is because their leaves resemble those of rosemary in shape, and are also edible. They are also described as native sage (as is prostanthera incisor, another strong-smelling edible native herb), because First Nations people all over the continent used them for smoking in ceremony.

Cassinias are dense here, because, like many of the common native plants that we now get in Wamboin, they are adept at stablising skeletal and damaged soils. They come in as helpers, holding everything together. There is a public path I walk most days, up a steep hill behind the house. As I walk it, I absentmindedly pull off leaves from cassinia quinquefaria and cassinia longifolia, crushing them, and feeling their strong oil on my fingers. Their scents are almost shockingly variable, some stink of curry, while others have that unmistakable limonene smell. Sometimes I cook with them: throwing them into trays of roasting vegetables, or once with Tamuz, making them the herbal centre of a homemade chilli oil. Other times, I dry them, and use them like I’d use sage: the smell is stronger, but harder to light. Often, I just place them in my clothes: a grounding scent to have as I move around the human world. Cassinia are a joy to live alongside.

Always was, always will be (Aboriginal Land)

I currently have the pleasure of being the operations officer for a fantastic event this week: Australian National University’s First Nation’s Composer’s Gathering. It’s set to be a very beautiful event, with some real luminaries of Australasian music performing, teaching, and sharing. Tickets are on sale above. And you can buy very affordable tickets to the individual concerts, here (Thursday the 27th), here (Friday the 28th), and here (Saturday the 29th).

Where you can catch me and my work

It's a busy time coming up.

On Saturday November 29, and Sunday November 30, I’ll be showing a few of my pieces in a small install at Garden States Regeneration: an ethnobotany conference hosted in Victoria this year. You can check out the participating artists here.

If you are in Melbourne, and inspired to book a last-minute ticket to the conference, you can do so here.

Next week, I will be in the art show Creative and Sensory Entanglements in a Multispecies World to accompany the MEAM (Multispecies Ethnography and Artistic Methods) Conference in Canberra. We will be exhibiting in the lovely Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW) Gallery, which I'm very pleased about. If you are in Canberra, and would like to come to the opening of the exhibition, you are warmly invited. The opening will take place on Wednesday December 3, 5.30-6.30pm in the CIW Gallery.

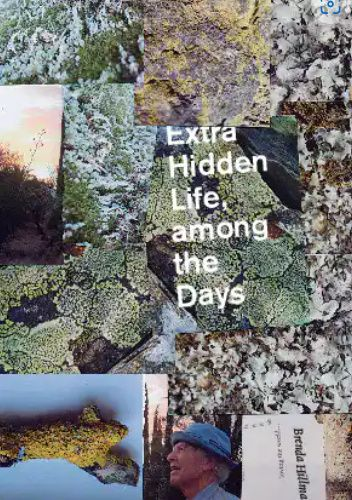

Your Christmas book list: Extra Hidden Life Among the Days, Brenda Hillman

I read an unusual amount. An almost wasteful amount. I read an amount that a psychologist might call “concerning”, and “definitely escapist behaviour”. If you catch me any time between 9pm and 7am, there is a good chance I am awake and reading. I am here to infect you too.

Buy for: Your poet friend. Your favourite anarchist. Your critical theorist cousin who is now obsessed with nature and talking about “retraining in botany.” I mean me. Go back in time and buy this book for me.

Pairs well with: Mary Oliver’s Devotions, Anne Boyer’s My Common Heart, unspeakable rage at capitalism, solastalgia, getting arrested in your senior years, translating the untranslatable Portuguese word “saudade”, noticing wildflowers.

It’s a tough call, but I think this is my favourite book of poetry. It lives permanently in my writing desk, so that I can reach for it every time I need to be reminded of what perfect wordsmithery looks like. Perfect wordsmithery looks like this: the knobs of song molecules fit into the frog.

It is an extraordinary book for multiple reasons. The first being the design and layout. Despite being published in 2018, and by a woman who was 69 at the time, the graphic design wouldn’t be out of place in a collection designed by zillenials. The dustjacket, which drew me towards the book in the first place, is a messy collage of lichen. The poems are interspersed with small photos, placed to break traditional layout conventions, such as on the edges of pages. These photos are also often of lichen. There are many concrete poems. The overall visual effect is a sense of verdant overflow and tactility.

Extra Hidden Life is also extraordinary for its ability to balance grief and levity. The book is steeped in loss: the first section, the Forests of Grief and Colour, is shaped around solastalgia; and the fourth section, Two Elegies, is a sweet ode to Hillman's recently-deceased father. And yet, it is quietly and enduringly funny. The poem titles give this away: Describing Tattoos to a Cop, Crypto-Animist Introvert Activism, Species Prepare to Exist After Money.

This balance between grief and humour is part of a wider project in the book: the project of finding ways to survive witnessing. Extra Hidden Life neatly marries blunt rage at ecocide and social injustice with wry prose:

[Safari cannot open page & Apple names

its systems after big cats that have been

murdered on safaris like Cheetah, Puma,

Jaguar,

Panther, Snow Leopard; the cats get bigger

the more they are destroyed]

This is not a book for everyone, I think it should be, I think it’s brilliant. But Brenda Hillman is very much a poet’s poet, and I understand that some readers find wordplay, and games with meter to be a little hard to digest. For those of us who love a multilingual romp through sounds, ellipses, grammar, and grief, it is a welcome resting place. For me, living at the edge of Mongarlowe, at the edge of a world charred by fire, it is a welcome companion to my own days in the forests of grief and colour.

Other good things

Dr Cat Kutay recently wrote a lovely piece for Decoloyarns: the decolonial publication I volunteer for. The piece is called Listening to the Ants, and was adapted from a conference session on Actor Network Theory–the theory that most of what we experience is created by complex networks of human and nonhuman actors. Beginning by describing what we learn by listening to ants, Kutay’s piece discusses the millenia-old practices of Indigenous Engineering and Epistemology, and invites us to adapt this richer, more networked approach in our own academic lives.

If you like this piece, you can also check out some of our other writing on decolonising a Science and Technology Studies conference.

Mutual Aid

I believe that one of the most important causes in Australia today is keeping First-Nations people out of the prison system and away from the police: systems where they are routinely treated with violence, even in Canberra. Yeddung Mura, Good Pathways, is a community-led Indigenous organisation that treats over-incarceration and recidivism at their root cause: trauma. Individuals who have been through the justice system are treated with yarning circles, culturally safe trauma treatment, and community engagement programs. They are also offered transitional accomodation, case management, chaplaincy, job-training, and parole support. You can donate to them here.

Thank you

If you feel moved by anything in the newsletter, and want to forward it to a friend, that would be so helpful to me.